In December 1992, Archie Karas walked into The Mirage in Las Vegas with $50 to his name and the kind of quixotic self-confidence known only to gamblers. Borrowing $10,000 from a fellow poker player, the 42-year-old Greek-American sat down at a poker table ready to make—or lose—millions. Within hours, he turned $10,000 into $30,000 and returned $20,000 to his now happy backer. He had his stake. The real action was about to begin.

What followed is the stuff of legend—a two-year streak so improbable, so brazen, that it’s simply known in gambling circles as The Run. Though details have blurred over time, as fact has melded with fiction, the story goes something like this: Archie crossed the street and challenged a wealthy, well-known professional gambler to games of pool with unheard-of-high stakes. In those initial games, Karas reportedly took over $1.2 million from “Player X” and began a streak so absurd that, at its peak, he had amassed $40 million in winnings. Nothing could stop the wild run.

That is, until the spring of 1995, when Karas went hard into baccarat.

You likely know where this is heading, but let’s say the quiet parts out loud anyway: there’s reason professional poker players typically avoid baccarat. Baccarat is a game where chance dictates results, not skill. “A stupid game,” Karas himself once said. “Doesn’t make sense. Everything is against you.”[i]

Furthermore, if you ever find yourself up $40 million after the greatest casino run of all time, there’s only one correct move: praise the gods of fortune, take your winnings, and go home. You’ve won the lottery.

But Archie wasn’t an investor. He was a gambler—and a proud one. “You’ve got to understand something: money means nothing to me,” he once told Cigar Aficionado. So, instead of banking millions, Karas lost everything in a matter of weeks, almost exclusively in baccarat. One night, he reportedly lost $11 million. Over two weeks, he lost another $20 million.

By mid-1995, his improbable fortune had been entirely squandered—lost to games he had no realistic hope of repeatedly winning.

Karas broke a cardinal investing rule: never sit down at a table where you can’t expect to come out ahead over many hands. Investors would do well to remember this lesson in today’s market climate.

Valuation: Determining Good Games

In investing, one of the biggest determinants of whether you’re sitting in a “good” game is valuation. Valuation— an estimation of the monetary “worth” of an asset (as distinguished from the “price” you happen to be paying for it) —is a major factor in long-term returns.

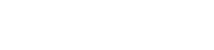

Why? It boils down to a simple reality: there tends to be a long-term relationship between price and perceived value. People generally have an idea of what something should be worth and are typically willing to pay within a range of that value, not beyond it… at least not forever. For example, many might say the Subaru Forester is a reliable car—but not worth a million dollars. They might indulge in a $5 Starbucks latte, but balk at a $20 cortado.

With stocks, we may examine valuation through various lenses. These can include discounted cash flow models, expected internal rate of return calculations, or the Price-to-Earnings (PE) multiple. The latter metric expresses the market price of a stock as a multiple of what the business is expected to earn next year. For instance, a stock trading at $40 per share that is expected to earn $2 of Earnings Per Share (EPS) next year would carry a PE multiple of 20x earnings. All else being equal, a lower PE multiple for a stock (or a stock market in aggregate) suggests a good deal is on offer, while a loftier multiple could warn of expensive conditions.

Over reasonable lengths of time, valuations exhibit a tendency to revert towards their historical mean – a sort of investment gravity. Valuations that soar beyond levels most perceive as reasonable tend to correct, and asset prices eventually fall back down. Sometimes, especially in periods of hype, gravity takes a while to kick in. But over hundreds of years of market data, one thing has held true: there’s always a level too high for buyers.

Like the casino, investment gravity always wins.

How the mechanics work

To illustrate how this works, imagine you come across a retailer you believe shows fantastic promise. Let’s call this company SuperMart. With hundreds of stores offering everything from groceries to electronics, SuperMart is rapidly gaining market share because of its ability to offer a wide range of goods at affordable prices. They can do so because of large and improving economies of scale in purchasing, marketing and distribution. This makes them a formidable competitor with a dominant competitive moat.

You believe SuperMart is expertly run and are confident it can grow its earnings at 10% annually for the foreseeable future (for context, the historical average growth rate of companies comprising the S&P 500 would be closer to 6-8%, depending on the economic environment, so this would be no mean feat). But would this confidence in the underlying business make SuperMart a great potential investment? It depends. That answer would strongly depend on the price, and implied valuation, you are paying for it.

Now consider: the long-term average PE multiple on the S&P 500 is on the order of 16x earnings. But let’s say that as a strong business with great prospects, SuperMart has tended to garner a premium PE multiple of 20x historically.

Imagine, however, the stock is priced at 40x expected earnings — a level, incidentally, that is not uncommon among quality, U.S. large-cap companies today. What would need to be true in the future to derive an attractive return on SuperMart stock and what are the odds of it being a good or bad investment?

The answer to that question would depend on two questions:

- Do SuperMart’s earnings grow as expected?

- Do investors remain willing to pay the same elevated multiple – 40x — on those earnings as before?

Here’s how the math breaks down across a variety of P/E multiples and growth scenarios:

We see that a lot must go right for a SuperMart shareholder to make a handsome return over the next five years. Earnings growth must impress, and the market must continue to be willing to pay a lofty multiple for the stock.

However, there are a wide array of outcomes, in which multiple compression and/or earnings disappointment occur, that would yield an underwhelming result: 65% of the scenarios we contemplated produce an expected return of 5% or lower.

And if investment gravity were to take hold, and the valuation of SuperMart were to retrace to its historical mean of 20x earnings – or below – the potential for a meaningful loss of capital looms.

In short, stocks that trade at higher price multiples can still win – it’s just harder. In the case of SuperMart, conceivably the multiple could hold up and growth could deliver as expected, leading to attractive returns. But there were also many more scenarios in which returns would be weak or poor. This is why we say valuation determines whether or not you’re in a good game. The higher the valuation, the more has to go right to win, and the more confident that you have to be in a company’s promised growth trajectory.

Finally, at some point, a high enough valuation means the number of scenarios in which you’d win becomes small and their probability unlikely. This tells you it is time to stand up from the table you are at and go find a new one.

Walmart and Cisco: real world examples

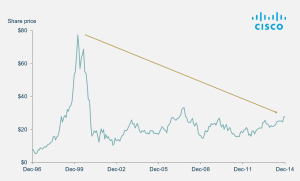

Walmart and Cisco at the turn of the century are prime examples of this phenomenon. From a fundamental standpoint, both were excellent companies. Walmart revolutionized how Americans shop with its one-stop destinations for groceries, clothing, and household goods at low prices. Cisco played a pivotal role in the rise of the internet, providing essential networking technology.

Both companies grew admirably: over the next fifteen years, from December 1999 to January 2014, Walmart and Cisco grew their earnings per share at nearly double the rate of the S&P 500 writ large.

But these strong business results belied the experience of shareholders. Walmart shareholders earned just 3.1% per year over that period (a better return could have been had in Treasuries). Cisco investors watched the stock decline by 89% as the DotCom hype receded and experienced an annualized return of -3.7%.

It is worth noting that the S&P 500, which traded at a 24x multiple in 1999 (a short distance from its valuation today), also underwhelmed investors. It returned just 4.2% per annum in the following decade and a half.

The lesson is clear: no matter how robust the underlying business, paying too high a price can lead to lackluster returns.

U.S. stock market

This brings us to the U.S. stock market, particularly its large-cap segment, which is currently trading at valuations well above historical averages. A prime example is the “Magnificent 7” – Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta, and Tesla – whose elevated price multiples reflect the market’s optimism. The current PE multiple on this cohort is nearly 30x, versus roughly 22x for the S&P 500 writ large and 17x for the median stock in the index.

That’s not to say these aren’t great companies—they are dominant for good reason. However, their lofty valuations leave little margin for error.

But it’s not just the Magnificent 7 trading at high valuations, either. Companies like Chipotle and Costco, while outside the tech sector, have also reached valuation levels that require consistent, extraordinary growth to justify. For example, Chipotle has been rewarded for its rapid expansion and operational excellence, but its price-to-earnings ratio of 45x, necessitates an almost flawless outlook for its future. Similarly, Costco —a retail powerhouse long admired for its scale and innovation—is trading at a PE multiple of 51x. This exceeds the 36x multiple it garnered in the heady times of the late 1990s. Such high expectations place immense pressure on these companies to deliver uninterrupted growth, leaving investors vulnerable to even small setbacks.

Could an investor still succeed with these high-priced companies? Certainly—just as you might win a hand of baccarat. In the short term, momentum could work in their favor, and the stocks might perform well. However, if the long-standing relationship between value and price holds—and markets ultimately revert to their historical norms—the odds for stocks priced like this become far less favorable.

Takeaways

The lesson here is simple: in investing, as in gambling, the odds of success are often determined before the game begins. High valuations demand near-perfect execution and uninterrupted growth to justify them, leaving little room for error. A company can be great and grow admirably for a decade and its stock can still move sideways (or worse).

While momentum can carry stocks higher in the short term, history reminds us that the gravitational pull of valuation eventually prevails. Winning in the stock market isn’t about betting on the flashiest names or chasing the hottest trends—it’s about sitting at the right table, paying a fair price, and letting time and fundamentals work in your favor.

Archie Karas lost it all because he gambled where the odds were against him. Investors would do well to remember: don’t sit down at a table where the odds aren’t on your side. Right now, this means remembering that, yes, valuation still does matter. Even, especially, when hype is strong – like now — there always needs to be a defensible investment case.

At the time this article was written, Microsoft Corporation was held by Focus Asset Management.

[i] Wall Street Journal. (2024, January 30). Archie Karas, a gambling legend who made—and lost—a fortune, dies at 73. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/arts-culture/books/archie-karas-dies-73-a581b4c6